SOMETHING

ABOUT THE HORSE.

753

high-priest and consul. Verus,

another Roman Emperor, erected a statue of gold to his horse, and fed him

with raisins and almonds from his own hand. When the creature died, he was

buried with great pomp, all the dignitaries of the empire attending; after

which, a magnificent monument was erected to his memory on the Vatican

Hill.

It was this high appreciation of

the horse which inspired the poet of the land of Uz, that made Solomon

liken his mistress for beauty “ to a company of horses in Pharaoh's

chariots.”

It is by viewing the horse only

in the light of a war-steed, or as an appendage of royalty, that we can

explain many passages, not only in the Old Testament but in the Greek and

Latin classics. Even during the Trojan war these animals were

exclusively in the retinue of princes, and were always associated with the

glorious forthcoming of kings. It is in times comparatively modern

that the horse has become a beast of burden; in the East, more

particularly in Arabia, he is still preserved from labor, save to carry

his master on his errands of pleasure, or with him engage in the strife of

war.

Homer represents that the horses

of Achilles wept for Patroclus, and makes those of Rhesus speak of their

good fortune. Aristotle mentions a horse of Sythia that precipitated

himself from the top of a high rock in order to punish himself for

committing a base act.

The Arab poet, Eldemire, relates

that the Calif Merouan had a horse that never permitted his groom to enter

his apartments without being called. The hapless fellow chancing one day

to forget this observance, the animal became indignant, and seized the

groom in his teeth and ground him against the marble of his

manger.

Pausanius relates that he knew a

horse that showed himself completely conscious of his triumphs, and

that whenever he won a prize in the race at the Olympic games, proudly

directed his steps toward the tribunal of the judges to claim his

crown.

Pride, which is eminently

becoming in the horse, sometimes in him degenerates into disdain.

Bucephalus, according to Plutarch, when once caparisoned, would let no one

approach him but Alexander.

Among the patriarchs of the

nomadic tribes the horse is still the intellectual companion of the chief,

occupying so large a share of his affections that his wife and

children hold a second place. The Arab repeats the immemorial

proverb, that “ He who forgets the beauty of horses for the beauty of

woman will never prosper,” and exulting in the favor of Ali, exclaims,

“Long tresses and long manes will be seen among us until the day of the

resurrection!“ The warrior caste still maintains its supremacy, and we

hear the lamentations of Abd-el-Kader, that many of the horses of the Arab

race have fallen from their nobility because employed in tillage, in

carrying burdens, and doing useful rather than ornamental work. He

declares that if the true horse even treads upon the plowed land he

diminishes in value, and illustrates the idea by the following

story:

“ A man was riding upon a horse

of pure blood when he was met by his enemy, also splendidly mounted. One

pursued the other, and he who gave chase was distanced by him who fled.

Despairing of reaching him, the pursuer in anger shouted

out,

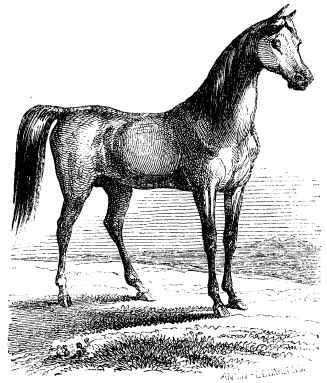

THE ARABIAN.

Whatever may be said to the

contrary, there is but one true horse in the world, and that is the Arab

stallion. His beautiful, nay, sublime description by Job, is the

inspiration of one who only sees what he describes in its most perfect

state—a thing you look at as you look at the stars, distant, but living

with glory. As with all the ancients, the horse in Job's mind was only

associated with royalty, spoken of as the attendant of princes, or

connected with the fascinating yet terrible accompaniments of war; for he

was never seen, as in our times, occupied in the familiar and beneficial

purposes of draught in our streets, and husbandry in our fields. A modern

reader, therefore, must enter into the sentiment and feeling of antiquity

in order to fully appreciate this description of the horse. The old

patriarch wrote it while sitting under his tent in the Arabian desert;

looking out from under its folds, he beheld all other domesticated animals

subservient and deformed by labor—the horse alone shone forth in its

primitive glory. We can imagine him in his pride as he stood before Job,

who, admiring, in the enthusiasm of the moment, asks,

“ Hast thou given to the horse

strength?”

The rays of an Oriental sun flash

along his silken coat, and he continues, “ Hast thou

clothed his neck with the thunder-flash?”

The noble animal displays its

energies in playful gambols, when Job, now full of enthusiasm, fairly

daguerreotypes the scene:

“ Hast thou made him to leap

forth like the arrow ? The glory of his nostrils is terrible; He paweth in

the valley, and rejoiceth in his strength.”

Vol. XIII.—No. 78.—3 B