SOMETHING ABOUT THE HORSE.

757

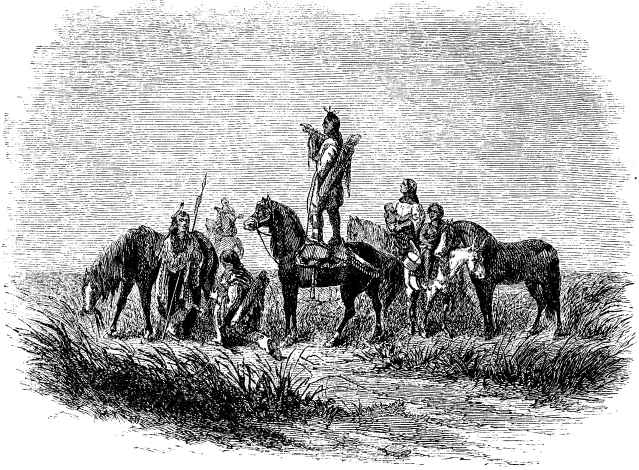

NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS AND THEIR PONIES.

quently the “ Indian pony”

possesses less intelligence than he would if he had a more

considerate trainer. When a chief dies they sacrifice his war-steed

over his grave, that he may go well-mounted into the presence of the “

Great Spirit.” The horse, to them, may be considered a vessel to

carry them over their boundless prairies, assist them in hunting the

buffalo, and aid them in their war excursions. Occasionally these

vast fields of vegetation, dried by the summer sun, ignite, and a

conflagration takes place such as can be witnessed nowhere else in the

world. On roll the devouring flames, crackling and exulting, while

the dark clouds of smoke obscure the sun and stifle the atmosphere. It is

on these occasions that the Indian and his horse have a chase for life;

and often, in spite of their combined sagacity and fleetness, they are

overtaken and destroyed.

The same natural causes which

operate to make the home of the horse and of man identical in our own

day, served to bring them together in the first ages of their

existence. The size of the brute rendered it conspicuous; and it is

presumable that he was at first hunted alone as a luxurious food. Compared

with the flesh of the horse that of the ox is coarse in the extreme,

the two presenting all the differences that distinguish the commonest

canvas from the finest cambric. The fibre of the horse is delicate,

and the colors it displays in its perfect form defy the pencil by their

beauty. The muscles of the horse are arranged more symmetrically

than those of any other animal, and the general aspect of the creature's

frame, upon dissection, enforces the idea of a beast of

supe-

rior order. Few have ever made

themselves practically acquainted with the beautiful mechanical

construction of the horse, without imbibing even a higher respect for

him than is realized by the superficial examination of his outside form.

But all this delicacy and beauty rather destroys than tempts the human

appetite, and this circumstance, added to the intrinsic value of the

horse, has discouraged hippophagy —a taste attempted to be revived by many

intelligent “savans” (?) in France. Acceptable as the flesh of the

horse may have been to the palates of the early representatives of

mankind, it is probable they were not able to indulge in an excess of this

kind of food. The animal was difficult to approach, and could hardly be

taken by surprise; once alarmed, pursuit was hopeless, and, in a close

encounter, the issue would be very doubtful. It is, therefore, probable

that the horse was captured by means of pitfalls and similar contrivances

peculiar to all barbarians. The carcass was alone desired—the life of

the victim was in no way regarded.

The Scandinavians and Germans,

devoted to the worship of Odin, raised with the utmost care, in the “

sacred pastures,” a breed of white horses destined for immolation to the

gods which they adored. Once sacrificed, the fumes of their roasting

carcasses were left for the “ superior beings;” the flesh was sensed

up at the festive board. From this custom probably originated

the taste for this kind of food which existed among all the nations of the

north, until Christianity penetrated Europe and succeeded in

destroying the custom, because it was supposed to be directly

connected with the rites of