762

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE.

The speed of horses has always

been a matter of admiration, and is invariably spoken of in the

language of hyperbole. The Orientals use the most beautiful and figurative

expressions when alluding to this subject; they say, “ Horses are

birds which have no wings;” “ For horses nothing is distant;” or, “My

steed possesses the wings of the wind.” Among the more matter-of-fact

people of temperate climates we find equal exaggeration, but expressed in

less poetical phrase. The meaning of “low down in the twenties,” is, if

analyzed, quite as improbable as to say that “for horses nothing is

distant.” The great Anglo-Saxon ideality, however, is to speak of a horse

going a mile in a minute, which is really the absurdest of fictions,

such a feat never having been accomplished, save by Pegasus, or by

the steeds of Phaeton, which dragged the chariot of the

sun.

Before the introduction of

railways the horse was the swiftest mode of conveyance man possessed

; when, therefore, extraordinary distances, within a given space of

time, were made by their assistance, or feats of a remarkable kind were

performed upon their backs, the details were heralded abroad as

“exciting news,” and solemnly recorded among the wonderful events of the

day. Among the famous things particularly remembered is the journey of a

Mr. Thornhill, an innkeeper, of Stilton, in Huntingdonshire, England,

who rode from that place to London, then back to Stilton, then again to

London, making a journey of two hundred and thirteen miles in twenty-four

hours. With the aid of several horses, this man made the same journey in

twelve hours and a quarter. Sir Robert Carey created an intense excitement

in his day by riding three hundred miles in less than three days, when he

went from London to Edinburgh to inform King James of Elizabeth's death.

It is noted by the chroniclers of the time, that the valiant horseman had

several falls, and received many sore braises on the way, which occasioned

his going battered and bloodstained into the “royal presence.” In

more modern times General Lafayette displayed his zeal and strength of

constitution by riding from his head-quarters, Rhode Island, to Boston,

nearly seventy miles, in seven hours, and immediately upon having an

interview with Washington, returning the same journey in six and a

half. On the 3d of May, 1758, a Die Vernon ventured a considerable wager

that she would ride a thousand miles in a thousand hours, and finished the

match in little more than two-thirds of the time. So delighted were the

country people at her success, that they strewed the road she passed along

with flowers. Seventy-five years ago it was very common to make bets upon

riding a long distance “in short time,” by constantly changing horses. In

this way a Mr. Wilde, an Irish gentleman, made himself temporarily famous

by making, over the Kildare course, one hundred and twenty-seven

miles in six hours and twenty minutes, winning a wager of a thousand

guineas. A man named

Nicks (Dick Turpin), having

committed a robbery about four o'clock in the morning, and

fearing detection, “ made for Gravesend, where he was ferried over

the Thames, and appeared the same night at eight o’clock on a

bowling-green in the city of York. Upon his trial he was acquitted,

the jury deeming it physically impossible for the same horse to bear

the same man three hundred

vales in sixteen hours.”

A highly interesting volume might

be written upon the garniture of the horse. It was not customary in

ancient times to shoe his feet with iron, according to our modern

practice, so that a strong hoof, “hard as brass,” and solid “as the

flint,” was reckoned one of the good qualities of the steed. In

Oriental countries the dryness of the soil made an artificial defense

of the hoof less necessary than in the mire and muddy ways peculiar to the

north of Europe. Necessity first suggested the shoeing of horses, and

custom confirmed the practice. There is historical testimony, that before

the use of metal horse-shoes the hoofs of the poor animals became

worn away during fatiguing journeys. When Mithridates was besieging

Cyzicus, he was obliged to dispense with the use of his cavalry, because

the hoofs of his horses entirely wore out. Diodorus Siculus, in speaking

of the army of Alexander the Great, states that on one occasion the

hoofs of the horses had become, by uninterrupted traveling, totally

broken and destroyed. Hannibal's cavalry, which were principally

Numidian, lost all their hoofs in the embarrassing march through the

swampy grounds between Trebia and Fesulae. The ancients had no saddles,

judging from all sculptures that have been preserved, yet they are alluded

to in Leviticus and in Numbers. Many rode without even a bridle, and

thus resembled the Indian tribes of our day, at least in this particular.

The sculptures of Kouyunjik and Khorsabad represent the riders

“bare-backed.” The Elgin marbles are also without saddles; but the

want of these things were more than compensated by other trappings,

particularly of the bridle and reins, which were of extraordinary

splendor. In the bas-reliefs found in Nineveh the trappings of the horses

and chariots are remarkable for their richness and elegance.

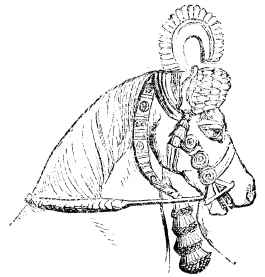

Above

HEAD-DRESS OF AN ASSYRIAN

WAR-HORSE.